Why do kids play sports?

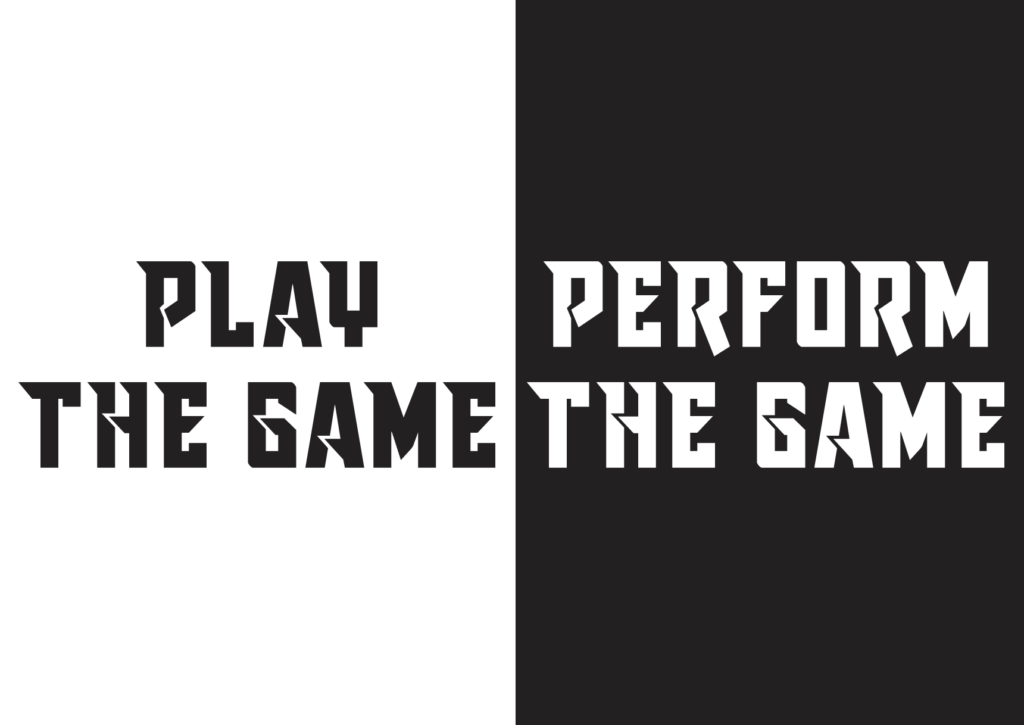

Along the years of growing Elite Athletes we have met many professional players in whom we noticed an unfortunate trait. The majority of them have stopped being players: they do not experience basketball as play anymore – it became a performance.

The best among them, or at least the healthiest pro athletes, we see are the ones that, even though they made their job of this game, they can still play! They move with a sense of lightness and open perspective to find ever-creative solutions. They still remember why they started and how they started on that neighbourhood playground. This trait inspires and is very noticeable.

So why do kids start playing sports? The research is clear, kids play sports because of three main things:

- Community: to have a sense of belonging and affiliation to a group of friends, to a team-spirit with shared values and aims

- Developing new skills: kids love to improve in things and learn new things

- To have fun: experiencing the dynamics, the action, challenges and novelty in sports

Low on the rankings of those results is winning.

There might lie a potential in a kid to become a professional player. Be that is it may, we should not be the pushing ones. Rather we are the ones that should stay “on top” of such projected hopes and dreams by creating an environment where the joys of playfulness and free exploration stay alive. In the long run this is of high priority if we want to create an environment that support long-term health, curiosity and joy for life.

This does not imply that training and games should not be challenging and demanding but it does mean that it should not fixate players into a belief that they only are valuable human beings when they win games and perform well based on an excel stats sheet.

When parents are unconscious of their own outwardly projected motivations and link the achievements of their children to their own moral worth, the child will perceive this.

Kids are not miniature adults and words cannot fool kids as well as they can fool adults. When parent’s verbal comments are not consistent with their non-verbal signals for example – what their body language communicates – then kids will sense the latter. It makes them feel unsafe. As Reich wrote in his work Children Of The Future, “It is, to repeat, the energy charge accompanying the ideas, and not the ideas themselves which counts.”

Connected to our topic here we could say that it is not exactly our words and actions that matter as they can be fabricated in any form quite easily: the core of our communication is that what lies behind our words and actions that matters in the sense that it is thát what is experienced by the child. Therefore if an unresolved conflict in oneself as a parent is the base from which communication in the sports environment originates, then it is this behind-lying message that will be transmitted as the meaning behind the words or actions.

As Rosenberg repeated often on the essence of what he called Nonviolent Communication: “the basic literacy of Nonviolent Communication are feelings and needs. And you learn to hear the feelings and needs behind any message.”

Therefore it is important that parents become self-aware of their expectations as they will be reflected onto the children. It is not because you are present at the game, that you do see your kid for who he or she is. If you are unconscious of the expectations you have of your child, there is a chance that you see your child through those expectations. If you are looking for a certain outcome you will tend to only see the success or failure of the manifestation of that outcome.

“When I was successful

in youth sports,

people told my father that

he was lucky to have

a child like me.”

Imagine what a line such as the one above might bring about in a child’s relationship with sports.

Consequently it is of value that parents get to know themselves in how they are reacting to different sports situations, how their children perceive these behaviors and what the long-term consequences might be of this interaction.

Behaviors might find their origin in personal negative sporting experiences or perceptions of a negative sporting environment hence it would be a great opportunity to transform this negative trend towards a nourishing one. One sports psychologist, Dr. Bridget Murphy, shares: “If you are guilty of pressuring behavior, your child may be too frightened to be honest in response to your questions. Thus, a careful, and often difficult self‐exploration is necessary.”

Beyond the chance for parents to understand themselves better through observation of their behavior in their child’s sports environment, another sports psychologist, Dr. John Sullivan turns the one having the learning opportunity around and says that “children have an opportunity to learn physical, mental and emotional self‐discipline from sports, and part of the learning process is watching how their parents act at a game.”

Sources of this three part series

Jay Coakley (2005), The Good Father: Parental Expectations

and Youth Sports

Jay Coakley (2010), The Logic Of Specialisation: Using Children for Adult’s Purposes

Jay Coakley (2011), Youth Sports: What Counts as Positive Development?

Daniel Coyle (2013), The Encyclopedia of Sports Parenting

Daniel Gould and Larry Lauer (2005), Understanding the Role Parents Play in Junior Tennis Success

Camilla J. Knight (2014), Parent Guide: Evidence-based strategies for parenting in organized youth sport

Camilla J. Knight (2015), Influences on Parental Involvement in Youth Sport

Dr. Stephen Porges (2018), How We Influence Our Children’s Nervous System, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNIozAiorZA

Dr. Wilhelm Reich (1984), Children Of The Future

PhD Marshall Rosenberg (2004), Teaching Children Compassionately: How Students and Teachers Can Succeed with Mutual Understanding

Anthony J. Ross, Clifford J. Mallett and Jarred F. Parkes (2015), The Influence of Parent Sport Behaviours on Children’s Development: Youth Coach and Administrator Perspectives

Pedro A. Sánchez-Miguel (2013), The Importance of Parents’ Behavior in their Children’s

Enjoyment and Amotivation in Sports

Jim Taylor (2011), Red Flags of Over-Invested Sports Parents

Michael P. Wasser (1982), Children in Sport: Participation Motives and Stress

Richard Weissbourd (2009), The Morally Mature Sports Parent

Olivier Goetgeluck is co-founder of Elite Athletes and has the role of Play-Perform Director at the Elite Academy. He is educated as an instructor at Fighting Monkey Practice. Follow Olivier through instagram @goetgeluck or connect at olivier.goetgeluck@eliteathletes.be.